La Scala Theatre Ballet Peer Gynt Review

April 11, 2025 | Teatro alla Scala – Milan, Italy

This year marks a decade since the premiere of Edward Clug’s Peer Gynt – a ballet adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s 19th-century play that ventures deep into the surreal and dissonant world of its elusive antihero.

Currently staged at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala, the ballet celebrates a unique milestone: its tenth anniversary in its tenth theater. I had the chance to witness the performance on Friday, April 11th, featuring the company’s primo ballerino, Timofej Andrijashenko, in the title role.

First performed in 1867, Peer Gynt is among the most celebrated works of Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. Its musical counterpart – the Peer Gynt Suites, composed by Edvard Grieg in 1875 – has arguably become even more iconic. Familiar pieces like “Morning Mood” and “In the Hall of the Mountain King” are recognizable across much of the Western world, thanks in part to their frequent use in popular media.

150 years later, the story finds new life in a contemporary ballet choreographed by Clug, of the Slovene National Theater. Clug reinterprets Ibsen’s narrative through choreography and restructures Grieg’s suites to match the movement.

You may also like...

American Ballet Theatre Sylvia Review: Because Love is Worth Chasing For

In Sylvia, Ashton repeatedly uses grand jetés in the ballet not only to bring out the huntresses’ characters, but also to convey the main point of his work.

ABT The Winter’s Tale Review: Familiar Steps, Fearless Chemistry

As The Winter's Tale unfolded, it was the combination of a large production team and the dancers’ deep commitment to character that gave the ballet its depth.

La Scala Theatre Ballet Peer Gynt Review

The story of Peer Gynt is framed in the structure of the classic hero’s journey – a young man who leaves home on a quest of self-discovery, confronting more inner demons than outer. Peer moves through both whimsical and realistic circumstances, and Clug embraces this ambiguity using stark, minimalist set design and movement that feels mechanical, yet spontaneous.

In doing so, the ballet transforms from a traditional linear narrative into a more psychological, cyclical experience.

Simply put, the plot follows a young Peer as he leaves behind a contemptuous mother, drifts through life in pursuit of romance and adventure – at one point even stealing a bride from her own wedding – while also capturing the heart of Solveig, a wedding guest who will become his true love.

His adventures take him into the Troll Kingdom, where he fathers a child with a troll and subsequently escapes to Morocco, evading all responsibility garnered from his previous affairs. Ultimately, he finds himself locked away in a psychiatric ward, forced to confront the weight of his inflated ego.

Throughout his journey, he’s haunted by visions of Solveig, presenting a constant regret for a loss of a simple life. It’s only when he returns home to Solveig that he begins to find a sense of redemption.

Andrijashenko delivered a mesmerizing performance as Peer Gynt, demonstrating a natural ability to act. His embodiment of the character is both grandiose and fragile, capturing the essence of a man in constant flux – slipping between roles of brash adventurer, guilt-ridden son, and deluded dreamer.

It is in Andrijashenko’s nuanced portrayal that we feel the turmoil of the “Gyntish self”, which Ibsen describes in his play as

“a sea of fancies, cravings and demands…what stirs inside my breast and makes me live my life as me” (Act IV, Scene 1).

From the first scene, the audience is given a glimpse into Peer’s distorted subconscious through a pas de deux with his mother, played by Alessandra Vassallo.

A particularly striking moment occurs when Vassallo leaps onto Andrijashenko, wrapping her body tightly around him – an image that suggests emotional entanglement and points toward Peer’s narcissism, dependency and deep-seated shame.

Vassallo’s portrayal of the mother is deliberately exaggerated, bordering on comical, yet beneath the humor lies a raw emotion that sets the pace for the rest of the ballet.

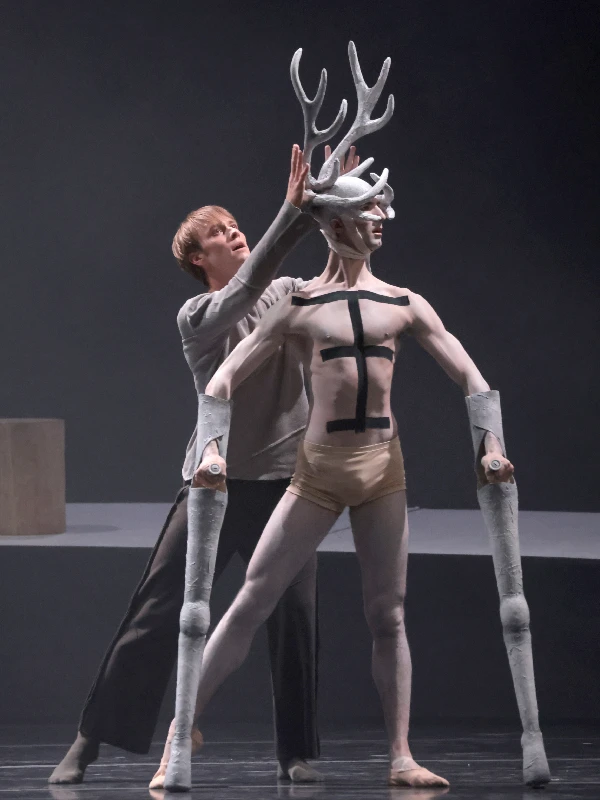

In Ibsen’s original play, a deer briefly appears during a dream sequence in the first scene, which quickly transitions to a more grounded reality. Clug, however, takes a deliberate alteration from this, opening and closing the ballet with the Deer’s hauntingly beautiful presence.

Portrayed by Emanuele Cazzato, with fluid precision (albeit dancing with his arms attached to stilts, reminiscent of a deer’s long frame), the Deer becomes a silent guide – part conscience, part observer – threading through the narrative with a subtle, non-verbal commentary.

The eternal presence of the Deer further boasts the idea that perhaps Peer’s journey is set in a dreamscape rather than reality, or even at times, a nightmare.

While the Deer watches from the shadows, Death, portrayed by Christian Fagetti, assumes a far more active and omnipresent role.

Fagetti moves in and out of the ballet seamlessly, at times interrupting the dance to alter fate, and at other moments, breaking the flow of movement with spoken lines. His effortless transitions create an unsettling presence, sparking curiosity in the audience with each unexpected appearance.

In an interview conducted by Carla Vigevani of Teatro alla Scala’s PR team, Clug explained that Death takes on the role of the choir from the original play – a kind of narrator, observing, commenting, and shaping the story from within.

Throughout the ballet, there is another character that appears and disappears like a figment rising from Peer’s subconscious: Solveig, his ultimate love interest, portrayed by Martina Arduino.

At first, she is met with casual indifference, both by Peer and the audience, and it’s not until the final pas de deux, between Andrijashenko and Arduino, that the full weight of Solveig’s significance is finally felt.

Arduino’s performance echoed the soft patience and quiet longing of her character throughout the play and shifted only in the end, when her restrained emotion unfolded.

In his first adventure, Peer finds himself in the Kingdom of Trolls. He becomes entangled in the seductive web of The Woman in Green (the Troll Princess), played by Caterina Bianchi.

A general sense of admiration filled the audience for Caterina Bianchi’s portrayal of La Donna in Verde, particularly during an unforgettable scene where she turned, flipping her green, viney hair to obscure her face and revealed a mask wrapped around the back of her head.

She then began to dance backwards, jutting her legs toward the audience, a mesmerizing display that fully embodied Clug’s mind-bending interpretation of the character. Her performance, both eerie and captivating, captured the surreal, otherworldly essence of the The Woman in Green.

The collective presence of the trolls, seemingly about 10 or 15, together with their towering King, created a gruesome atmosphere with their bizarre costumes and unsettling movements. Their exaggerated features and unpredictable choreography only deepened the sense of chaos and menace.

As the stage transforms into Peer’s next adventure, Clug makes effective use of humor – not to complicate the narrative, but to reveal and distill character.

In this particularly clever moment, as Peer dreams of marrying Solveig, he decidedly drops the wedding ring into the slot of a toy airplane rather than onto his finger, as though the ring was arcade currency. He then climbed inside the plane, rocking back and forth with the demeanor of a restless child, while Solveig drifted away and a Moroccan mirage slowly began to form.

In Morocco, Peer is now a grown, successful businessman. Andrijashenko danced in a suit and became surrounded by ballerinas gliding across the stage on rugs, as extensions of the rugs themselves. It’s a scene filled with opulence and whimsy, but to the audience, the success is short-lived.

Soon, the vibrant fantasy gives way to the sterile confines of a psychiatric ward, where Peer is forced to confront the unraveling of his own mind, and finds himself torn from his suit into rags.

It’s in the ward that Peer is meets the Four Lunatics, portrayed intensely by Maria Celeste Losa, Denise Gazzo, Saïd Ramos Ponce, and Domenico Di Cristo. Their performance was raw and unsettling.

A special mention goes to Losa, whose physicality and steadfast commitment to character left a lasting impression.

In this scene, Clug’s artistic direction shone brightly, and Andrijashenko’s performance was bone-shakingly powerful, embodying a spiraling mind, a broken spirit, and an ongoing internal battle.

In a poignant solo, Andrijashenko danced with his hands wrapped around his head, forming a crown – a subtle but powerful symbol of the remainder of his shattering ego and delusions.

He struggled fiercely, ultimately breaking free from his crown, only to be met with a line of psychiatric patients running to cling to his midriff, an eerie reminder of the weight of his own power and everlasting turmoil.

Shortly after, the psychiatric ward dissipates, and Andrijashenko becomes drenched in a cloud of white powder, leaving behind the ghostly trace of his movements on the stage for the remainder of the ballet.

It’s in this spectral state that he reunites with Arduino – as Solveig – for the final pas de deux.

For me, this was one of the most captivating moments of the performance: a culmination of pain, memory and quiet redemption.

Perhaps the powder symbolized the remnants of the self that Peer had shed – or destroyed – throughout his journey, now reduced to dust.

The audience was made to reflect as the two exited hand in hand through a door bathed in a heavenly, fog-filled light -a moment left open to interpretation: salvation, death, a dream or simply peace at last.

The final figure to remain on stage is the Deer who silently leaves his stilts at the door frame, before the curtains close.

In Clug’s Peer Gynt, the line between fantasy and reality, memory and identity, is delicately blurred. It is a ballet that doesn’t offer easy answers, but instead invites the audience to sit with ambiguity through scenes that were sometimes convivial, sometimes haunting.

Between Andrijashenko’s extraordinary portrayal of Peer and Clug’s poetic vision, the story of Peer Gynt becomes less a hero’s journey than it is a meditation on the self, a trip of the mind.

It was a performance that held the audience in rapt attention until the final moment – and maybe even wondering, “What just happened?”, in the best possible way.

Featured Photo of La Scala Theatre Ballet‘s Martina Arduino and Timofej Andrijashenko in Edward Clug’s Peer Gynt. Photo by Brescia-Amisano © Teatro alla Scala.